A Heavy Dose of Viagra Boys

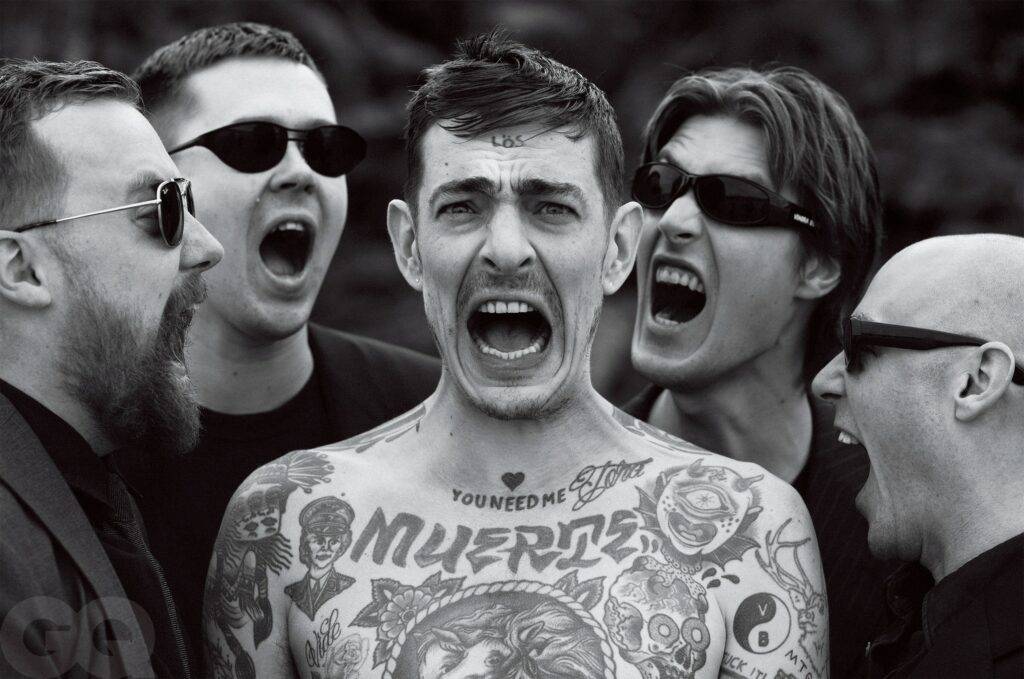

Viagra Boys (from left) drummer Tor Sjödén, saxophonist Oskar Carls, Murphy, keyboardist Elias Jungqvist, and bassist Henrik Höckert let out a primal scream.

A Heavy Dose of Viagra Boys

Sweden’s new punk-rock hell-raisers have made their name skewering toxic masculinity, die-hard

sports fans, right-wing fanatics—and themselves.

Lead singer Sebastian Murphy on the Stockholm waterfront

“Half of it is an act, and half of it is like a diary in a way,”

Murphy says of his work. “I don’t do it consciously, but

subconsciously it becomes a satire of myself and others.”

That disdain for right-wing extremists and their boorish patriarchy in decline is fully manifest on Welfare Jazz, the alternately narcotic and blistering new Viagra Boys album, they’re second full-length since 2018. Their debut LP, Street Worms—along with their bleakly humorous, semi-narrative music videos—garnered them a cult following, and three years later, when seemingly all mainstream manliness comes with a ramekin of extra toxicity on the side, the Viagra Boys’ brand of social punditry seems poised to break through to a wider audience. On brooding, pulsing tracks, Murphy proves himself an expert chronicler of the darker corners of the male brain, dissecting masculinity in all its ridiculousness while he sings in character as one of the hapless shitheads he’s criticizing. “I don’t need no woman telling me when to go to bed,” he wails on “Toad,” later explaining, “because I’ve been living on the outskirts of society my whole life.” It’s a grim continuation of the themes he explored on “Just Like You,” a highlight from Street Worms. Murphy spends most of the song drawing about pleasantries like the little dog he and his loving wife have in their nice house. But there’s a sneer in his voice and a bitter pill embedded in the dreamlike lyrics. At the end, our narrator is happy to wake and find himself back in his real, dismal life, his “never-ending hate for this completely fucked-up society” intact. “Thank God I never went to school,” he concludes. “Thank God I didn’t end up just like you.

Murphy’s lyrics pull off the difficult trick of balancing his performing persona with his role as trenchant observer. “It’s 50–50,” he says. “Half of it is an act, and half of it is like a diary in a way. I don’t do it consciously, but subconsciously it becomes satire of myself and others.” This kind of darkly humorous character-based lyricism places Murphy in a proud lineage. He cites as strands of his own creative DNA “a lot of country artists and the kind of old punk that incorporated comedy into the lyrics—not just anger and depression.” In fact, the new album ends with a lumbering, unsettling cover of John Prine’s “In Spite of Ourselves,” with Amy Taylor from Australian punk rockers Amyl and the Sniffers taking on the part that Iris DeMent sang in the original. It’s one of those transcendent songs that proudly celebrate love among the fallen class, and it serves as the perfect capstone to Welfare Jazz.

It’s also a testament to Viagra Boys’ range. On the new album, their sound is often as heady as it is hardcore, a sometimes trance-inducing, slow-burn music that blends elements of electronica and lo-fi with more classic punk. “It’s really about finding a groove you want to play for half an hour,” says saxophonist (that’s right, saxophonist) Oskar Carls. “In that way it’s like dance music. The band itself is not so much in focus; it’s more about the vibe—but not in a hippie way,” he clarifies. “Yeah, it’s not hippie—let’s make that very clear,” says drummer Tor Sjödén, raising an admonishing finger into the air.

Oh, and about that album title: “Welfare Jazz is like free jazz—the kind of music you can’t live on,” says Höckert. So it’s a defiant statement, a way of saying that Viagra Boys will play the music they want, regardless of whether it leads to rent payments or not. And it hasn’t, at least not yet. Everyone in the group maintains day jobs, and happily so. Murphy is an accomplished tattoo artist whose commissions blessedly haven’t dried up during the pandemic. Höckert is a carpenter and thus, similarly, is in a business that has been able to boom lately. “Nothing’s changed for me,” he says. “People actually want to renovate more than ever since they’re home all the time.”

Murphy says he’s also been moonlighting a little, contributing lyrics and guttural incantations to a recent album by his friend Isak Hedtjärn’s free-jazz group. “It’s a bit like spoken word,” he says. “Captain Beefheart-y stuff.” Writing lyrics across genres has made him reflect anew on his songwriting and on the stories he tells on Welfare Jazz. Just as much as the album is a critique of doomed patriarchy, he explains, the songs are fueled by sober self-examination—a hard look at the ennui and guilt that followed a recent breakup. “The whole relationship, I was taking speed every day and kind of lying about it,” he says. “Once we broke up, I realized what an asshole I’d been, and I regretted everything and wanted to do it all again. But it was too late.” Fortunately, Murphy is an old hand at pulling art out of his nosedives. As he puts it, “The only way I can go forward is by fucking up.”

Jesse Pearson is the founder and editor of ‘Apology’ magazine and the host of the ‘Apology’ podcast, where he talks with various cultural figures about books and reading.

A version of this story originally appears in the February 2021 issue with the title “A Heavy Dose of Viagra Boys.”

PRODUCTION CREDITS:

Photographs by Anton Corbijn

Grooming by Nenad Vukasin[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Responses