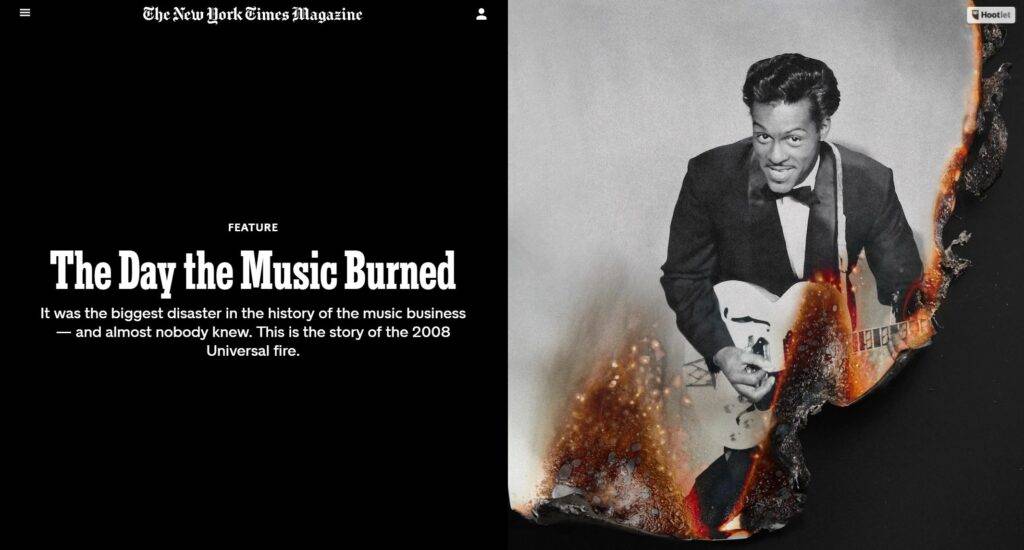

Terence Trent D’Arby – Now Sananda Maitreya

Why Terence Trent D’Arby became Sananda Maitreya: ‘It was that or death

“I moved some people in high places” … Sananda Maitreya, formerly known as Terence Trent D’Arby. Photograph: Michela Zizzari

In 1987, his debut album saw him hailed as a rival to Michael Jackson and Prince – but then his star crashed and burned. He talks about the nervous breakdown that triggered his identity change, living as a recluse and the music industry’s ‘Olympian’ conspiracy to bring him down.

Then Sananda Maitreya references his previous life as Terence Trent D’Arby, he looks uncomfortable. He even says “he”, not “I”, as though he is talking about a different person.

“You know, I had no choice,” he explains. He is sitting in the intense afternoon heat on the upper terrace of an apartment in central Milan, where he has lived for several years with his Italian wife, the architect, and former television presenter Francesca Francone and their two young sons. “People ask: ‘Why did you change your name?’ When you have a psyche that’s no longer functional, you petition another psyche. You either die – you kill yourself – or you think: ‘No, I’ve got more to do.’

“I was always Sananda Maitreya,” he continues, “and he [D’Arby] was assigned the role of this other form, which he performed until they pulled the plug on him. They didn’t pull the plug on Sananda; they pulled the plug on that particular script and psyche.” He sighs wearily.

“I don’t do many interviews,” he admits, describing the effects of his ordeal in the music business in terms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). “I guess I stayed away because I didn’t want to face it. PTSD can strike at any time and you have to deal with it. I can’t blame drugs, I can’t blame alcohol. The dude didn’t just change his name to be clever. It was that or death.”

Thirty years ago, D’Arby, an American of Scots-Irish “hillbilly” and Native American parentage who spent time in the army in Germany before launching his career in London, was the toast of Britain. Androgynously beautiful and sexually magnetic, he was a singer-songwriter and multi-instrumentalist who modeled himself on Muhammad Ali, a quote machine who declared himself a genius without too much prompting.

His debut album of sweetly rasping vocals and catchy rockin’ soul, Introducing The Hardline According To Terence Trent D’Arby, sold 1m copies in three days in the UK, spent nine weeks at No 1 over the next eight months, and 45 weeks in the Top 40. There were ubiquitous hit singles – Sign Your Name, Wishing Well, If You Let Me Stay – enabling D’Arby to assume his position on “Mount Olympus” (his phrase) next to the biggest stars of the day. He received the approbation of everyone from Miles Davis to Mick Jagger and mixed in the most rarefied circles: reluctantly, he cites Jack Nicholson and Princess Diana as examples of celebrities “whose patronage I was humbled to receive”.

“I moved some people in high places,” he cautiously allows, aware that hubris was one of the things that did for him first time round.

As a coping strategy, he imagines his rapid rise, and vertiginous descent, as a matrix of conspiracy theory and quasi-mythology (his latest album – a triple – is titled Prometheus & Pandora). After the relative failure of his second album, 1989’s Neither Fish Nor Flesh, D’Arby was effectively and unceremoniously “tossed off the mountain”. More expansive (and less tuneful) than his debut, critics viewed it as simple artistic overreach, while the public largely concurred: it shifted a fraction of the sales of its predecessor.Me and Master Michael Jackson had to play out the Apollo/Mercury scenario: him being the entrenched god, me the upstart

As Maitreya understands it, there just wasn’t enough room for another black superstar operating in the realm of poppy, soulful R&B, especially one as resistant to racial narrowcasting as he was and is (the vest he is wearing today pointedly bears the legend “Rock Star”). It was, he says, a “limited plinth”, and either he, Prince or Michael Jackson had to vacate.

“Me and Master Michael [Jackson] had to play out the Apollo/Mercury scenario: him being the entrenched god, me being the upstart who basically got sacked as a service to Apollo,” he says. Part of “a continuum of artists who carried the baton for as long as they could before they were killed, physically or psychologically”, he was, he says, “crucified”. By whom?

“I happen to know there were a couple of people in very, very high places in the establishment who, like Zeus, were kind of amused at my little routine,” he proclaims. “And it was working. Everybody was cashing in and happy as fuck. But,” he adds, switching once more to the third person to discuss himself as D’Arby, “behind his back, more and more A-list stars were complaining about the attention he was getting. The other gods on Olympus were sending their managers to ask: ‘What’s going on?’ The establishment had to do something about it because it couldn’t have all the gods angry.”

Whether Maitreya has constructed this meta-narrative to keep himself sane, or to rationalize his decline and fall without implicating himself artistically, isn’t clear. But he certainly stands by it. Asked whether he truly believes he was maneuvered out of the music business at the behest of several internationally famous musicians (or, at least, their record company: he, Jackson and, for that matter, George Michael were all on CBS), he replies: “I was a political sacrifice. This isn’t my theory. I’m telling you.”

Maitreya was born as Terence Trent Howard in Manhattan in March 1962. He later took his stepfather Reverend JB Darby’s surname, adding his own apostrophe. But his creative birth came 18 years later, during a dream that he had on the night John Lennon was murdered. “I had a premonition,” he recalls. “I was on a street corner in New York, and I saw him coming towards me. As he did, he had his hand out and seemed to recognize me. Then he disappeared into me.

From that point on, he could feel himself galvanized by the spirit of the late Beatle. Seven years later, he would proclaim Introducing The Hardline According To … as the greatest pop LP since Sgt Pepper.

Maitreya has pinpointed the moment of his “death” as D’Arby as 1989, following the disastrous reception to Neither Fish Nor Flesh. D’Arby would have been another 27-year-old inductee to that notorious “stupid club” alongside Kurt Cobain, Jimi Hendrix, Brian Jones and the rest.

That was the time he found himself, having fled London for Los Angeles, holed up in a mansion on Sunset Boulevard, living the life of a tormented recluse. Although his albums Symphony Or Damn (1993) and Vibrator (1995) had enjoyed a modicum of success, there was a sense of yesterday’s man about D’Arby, while the motormouth baton had been passed to a pair of Beatles buffs with equally massive self-belief.

“When they broke huge I felt like: oh, shit, they’re living my script,” he says of Noel and Liam Gallagher (the latter is alleged to have taken the name for his pre-Oasis band, The Rain, from a track on Introducing The Hardline …). “Was I jealous? It wasn’t a jealousy thing. It was more a loss – you can never have another beginning.”

Which was the more perilous time: late-80s London, when he was scaling the heights, or mid-90s LA when he was dejected and alone? He pauses before replying.

“London was emotionally more perilous,” he says, finally. “Los Angeles was more instinctively perilous. The system is very well regulated in LA. It’s designed to disconnect you from whatever your idea of yourself is. If you’re among devils and they realize you’re not a devil-like they are, there’s gonna be some great discomfort. LA is definitely one of the outposts of Mount Olympus. They weed out anyone who might be a threat.”

With La Toya Jackson in the late 80s. Photograph: Images Press/Getty Images

After talking in riddles, he adds more explicitly: “I think I cheated death half a dozen times while I was there.” Care to elucidate? “I had my house set on fire while I was in it,” he recalls with disarming nonchalance.

The next day, in a series of detailed (and high-flown) emails responding to specific points arising during the interview, Maitreya elaborates: “It felt as though I was living in someone else’s dream that had become a nightmare. My 12 years in Los Angeles were HELL! But I was sent to study hell and to learn as much from it as I could because there is no other place like hell for a full and complete education.”

D’Arby’s sojourn in Hades wasn’t pharmacologically enhanced: “Pot is the only thing I’ve been drawn to,” he reveals. “I certainly did ecstasy back in the day, and I liked mushrooms, but I was never really drawn to heavy drugs like heroin or cocaine.” But he did suffer a complete mental breakdown, one that necessitated a full-scale regeneration as Sananda Maitreya.

Does he ever wonder whether he might have avoided many of his troubles by simply recording Introducing The Hardline … Volume 2? “No,” he says. “More than likely that would have accelerated my death.”

Not that his rebirth as Maitreya has created a benign version of D’Arby. Just because his new surname has Buddhist connotations, this isn’t Cat Stevens morphing into Yusuf Islam. “The brusque, bold, audacious fucker – that was me,” he says, but he still is, even if the old energy goes in different directions.

The new album, Prometheus & Pandora, is a 53-track smorgasbord of rock, funk, soul, jazz and psych, “written, arranged, produced, performed & conceived by Sananda Maitreya”, as the credits boast, and released on his own label to boot. It might go lyrically off-piste to accommodate his grand allegorical vision, but as Maitreya insists: “These myths and legends continue to resonate inside all of us.” And besides, it’s not all godlike: there’s even a track, from the former sexual supremacist, about impotence, called Limp Dick Blues.

Onstage in 1989. Photograph: Tim Hall/Redferns

“Well, there you go,” he says. “When was the last time you heard a pop idol admit that they were having dysfunctional issues? Never! I’m counterintuitive like that.”

His hospitable wife, who has been listening in to most of the three-hour interview, in between supplying us with drinks and providing a generous spread for lunch, winks then laughs. “It’s just a song,” she says, indicating her husband’s priapic prowess and the continued functioning of his organs. “All of it works.”

Witty, waspish, a former trainee journalist who knows the value of a self-aggrandising (or self-deprecating) bon mot: he has been much missed. Has he missed us? “Do I miss being on the mountain?” he inquires of Olympus and its inhabitants, many of whom (Jackson, Prince, George Michael) are no longer here. “That none of my colleagues survived?”

Prometheus & Pandora is actually his eighth album as Maitreya, although there does seem to be a greater keenness to push this one. Does he want to be back in the fray?

“I didn’t make this album to be back in the fray,” he retorts. “I still have Madonna’s number. I can still call her and go: ‘What’s up, bitch? What’s going on?’” As his emails attest, “bitch” is a catchall for associates, male and female. Not that he’s overly preoccupied with what people think these days. When I ask whether he thinks his new music is, lyrically, too esoteric for mass consumption, he answers, “Maybe it’s not meant for mass consumption.” Touché.

“I don’t have to worry about what the average record company person thinks because I am the record company person,” Maitreya says as the interview comes to an end. “I’m not asking for any bitch’s permission to be what I am. God has blessed me with a good life, despite all the shit. I’m not begging on the street. There’s no excuse for me not to just fucking go for it. None!”

Prometheus & Pandora is released by Treehouse on 13 October

Responses